In the first article[1] of this two-part blog series, we looked at how frequently domains were used by bad actors for phishing activity across individual top-level domains (TLDs) or domain extensions, using data from CSC’s Fraud Protection services, powered by our DomainSecSM platform. In this second article, we analyze multiple datasets to determine the highest-threat TLDs, based on the frequency with which the domains are used egregiously for a range of cybercrimes.

In this deeper dive, we look at the following datasets:

- Spamhaus’ 10 most abused TLDs[2], reflecting information in its domain blocking list and containing domains with poor reputations (generally those found to be associated with spam or malware).

- Netcraft’s 50 TLDs[3] with the highest ratios of cybercrime incidents to active sites, generally reflecting phishing and malware incidences.

- Palo Alto Networks’ 10 TLDs[4] with the highest rates of malicious domains, reflecting four categories of malicious content (malware, phishing, command and control (C2), and grayware), and expressed as the median of the absolute deviation from the median (MAD).

- Data from CSC’s Fraud Protection services, as discussed in part one of this series.

Each dataset measures the proportion of domains across each TLD deemed to be associated with threatening content[5]. For datasets 1, 2 and 3 as outlined above, proportions are expressed as the total number of domains analyzed for the TLD in question.

Methodology: For ease of comparison, the threat frequency for each TLD within each dataset is again normalized, so that in each case the value for the highest-threat TLD is 1. The overall threat frequency for a TLD is then calculated as the average of the normalized scores across the datasets in which it appears. We excluded any TLDs from the results that were only present in CSC’s dataset and where fewer than 50 phishing cases were recorded.

Analysis and discussion

The above methodology yields the following list in Table 1 for the top 30 highest-threat TLDs, ranked by overall normalized threat frequency.

| TLD | Threat frequency | Registry | Operator[6] | Region (country) or type |

| .CI | 1.000 | Autorité de Régulation des Télécommunications; TIC de Côte d’lvoire (ARTCI) | Autorité de Régulation des Télécommunications; TIC de Côte d’lvoire (ARTCI) | Africa (Ivory Coast) |

| .ZW | 1.000 | Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (POTRAZ) | TelOne Pvt Ltd | Africa (Zimbabwe) |

| .SX | 0.945 | SX Registry SA B.V. | Canadian Internet Registration Authority (CIRA) | Caribbean (Sint Maarten) |

| .MW | 0.862 | Malawi Sustainable Development Network Programme | Malawi Sustainable Development Network Programme | Africa (Malawi) |

| .AM | 0.608 | “Internet Society” Non-Governmental Organization | “Internet Society” Non-Governmental Organization | Asia (Armenia) |

| .DATE* | 0.506 | .DATE Limited | GoDaddy® Registry | New gTLD |

| .CD | 0.391 | Office Congolais des Postes et Télécommunications (OCPT) | Office Congolais des Postes et Télécommunications (OCPT) | Africa (Democratic Rep. of the Congo) |

| .KE | 0.381 | Kenya Network Information Center (KeNIC) | Kenya Network Information Center (KeNIC) | Africa (Kenya) |

| .APP* | 0.377 | Charleston Road Registry Inc. | Google® Inc. | New gTLD |

| .BID* | 0.361 | .BID Limited | GoDaddy Registry | New gTLD |

| .LY | 0.356 | General Post and Telecommunication Company | Libya Telecom and Technology | Africa (Libya) |

| .BD | 0.351 | Posts and Telecommunications Division | Bangladesh Telecommunications Company Limited (BTCL) | Asia (Bangladesh) |

| .SURF* | 0.325 | Registry Services, LLC | GoDaddy Registry | New gTLD |

| .SBS* | 0.250 | ShortDot | CentralNic | New gTLD |

| .PW | 0.240 | Micronesia Investment and Development Corporation | Radix FZC | Asia (Palau) |

| .DEV* | 0.222 | Charleston Road Registry Inc. | Google Inc. | New gTLD |

| .QUEST* | 0.209 | XYZ.COM LLC | CentralNic | New gTLD |

| .TOP* | 0.196 | Jiangsu Bangning Science and Technology Co., Ltd. | Jiangsu Bangning Science and Technology Co., Ltd. | New gTLD |

| .PAGE* | 0.195 | Charleston Road Registry Inc. | Google Inc. | New gTLD |

| .GQ | 0.192 | GETESA | Equatorial Guinea Domains B.V. (Freenom) | Africa (Equatorial Guinea) |

| .CF | 0.168 | Societe Centrafricaine de Telecommunications (SOCATEL) | Centrafrique TLD B.V. (Freenom) | Africa (Central African Republic) |

| .GA | 0.164 | Agence Nationale des Infrastructures Numériques et des Fréquences (ANINF) | Agence Nationale des Infrastructures Numériques et des Fréquences (ANINF) (Freenom) | Africa (Gabon) |

| .ML | 0.157 | Agence des Technologies de l’Information et de la Communication | Mali Dili B.V. (Freenom) | Africa (Mali) |

| .BUZZ* | 0.149 | DOTSTRATEGY CO. | GoDaddy Registry | New gTLD |

| .CYOU* | 0.141 | ShortDot | CentralNic | New gTLD |

| .CN | 0.130 | CNNIC | CNNIC | Asia (China) |

| .MONSTER* | 0.106 | XYZ.COM LLC | CentralNic | New gTLD |

| .BAR* | 0.104 | Punto 2012 Sociedad Anonima Promotora de Inversion de Capital Variable | CentralNic | New gTLD |

| .HOST* | 0.101 | Radix FZC | CentralNic | New gTLD |

| .IO | 0.085 | Internet Computer Bureau Limited | Internet Computer Bureau Limited | Asia (British Indian Ocean Territory) |

*Extensions where there are currently no customer domains under CSC’s management.

Table 2 shows the datasets in which each of the top 30 TLDs appear.

| TLD | Spamhaus | Netcraft | Palo Alto Networks | CSC |

| .CI | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| .ZW | ✓ | |||

| .SX | ✓ | |||

| .MW | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| .AM | ✓ | |||

| .DATE | ✓ | |||

| .CD | ✓ | |||

| .KE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| .APP | ✓ | |||

| .BID | ✓ | |||

| .LY | ✓ | |||

| .BD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| .SURF | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| .SBS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| .PW | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| .DEV | ✓ | |||

| .QUEST | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| .TOP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| .PAGE | ✓ | |||

| .GQ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| .CF | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| .GA | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| .ML | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| .BUZZ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| .CYOU | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| .CN | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| .MONSTER | ✓ | |||

| .BAR | ✓ | |||

| .HOST | ✓ | |||

| .IO | ✓ |

It’s significant that this list is dominated by extensions from Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, as well as several new gTLDs. The latter is consistent with the observation that new gTLDs tend to be disproportionately more abused than legacy TLDs, although they tend to have better processes for tackling infringements[7]. Nearly half of the TLDs in this list are operated by just three organizations, namely CentralNic (six TLDs), Freenom (four), and GoDaddy Registry (four)—all consumer-grade registrars.

The Anti-Phishing Working Group’s (APWG’s) comprehensive Global Phishing Survey[8] of 2017, which analyzed the TLDs most frequently associated with phishing domains, also showed some similar trends (although the landscape may have changed somewhat since 2017). Its top 10 TLDs by frequency of phishing domains was dominated by African and Asian country-code TLDs (ccTLDs), with three of the top five (.ML, .BD and .KE) featuring in our top 30 list.

The below observations from the analysis are also notable:

- Some of the TLDs in the list have special significance:

- .LY – The frequency of this extension’s use in conjunction with threatening content is strongly influenced by its appearance in URL-shortening services (e.g., bit.ly, cutt.ly and ow.ly). This means its threat frequency is disproportionately large compared with what would be expected from its use solely as a ccTLD.

- .IO – The .IO extension is popularly used in domains with technology-related content, particularly anything associated with the range of Apple (iOS) operating systems. Many of the threat sites in this analysis are on compromised .IO domains, or subdomains of sites such as github.io, rather than reflecting any factors related to the British Indian Ocean Territory.

- The top 30 highest-threat TLDs includes four of the five free extensions offered by Freenom (with the exception of .TK, where the threat frequency is likely to be diminished by the large absolute number of registrations across the TLD). Their business model allows customers to register domains for free, with the option to make subsequent payments, depending on how the domain will be used. This makes these extensions particularly popular with phishers, who may discard their domains after a few days’ use for a phishing attack.

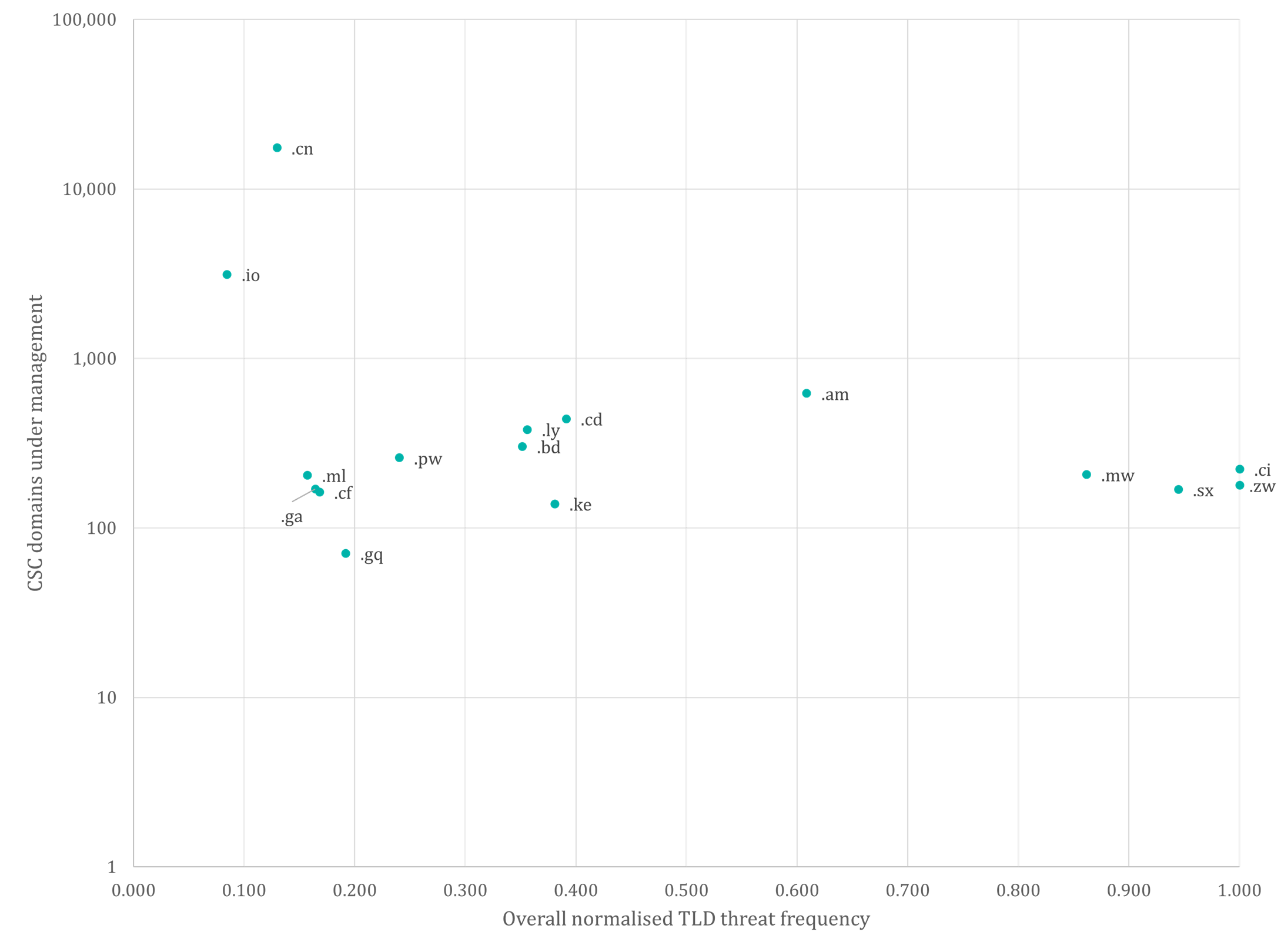

Figure 1 shows how the threat scores compare with the total number of customer domains under CSC’s management across the observed TLDs[9].

It’s notable that most of the highest threat TLDs are associated with only small numbers of domains under CSC’s management. Therefore, one clear recommendation is that brand owners may want to consider defensively registering domain names featuring high-relevance brand terms across the high-risk extensions where possible, to prevent them from being fraudulently registered by third parties.

When exploring a defensive registration strategy, brand owners should also consider registering domains containing specific brand variants or keywords that are frequently associated with phishing activity, rather than just registering exact brand matches across TLDs of particular concern. These might include common character replacements, keywords like “login”, “jobs”, “invest” or other industry-related keywords.

Where relevant domains have already been taken across high-threat TLDs, it may be advantageous to monitor them for possible future changes in content, or to launch enforcement actions or acquisition processes in cases where infringing content is identified.

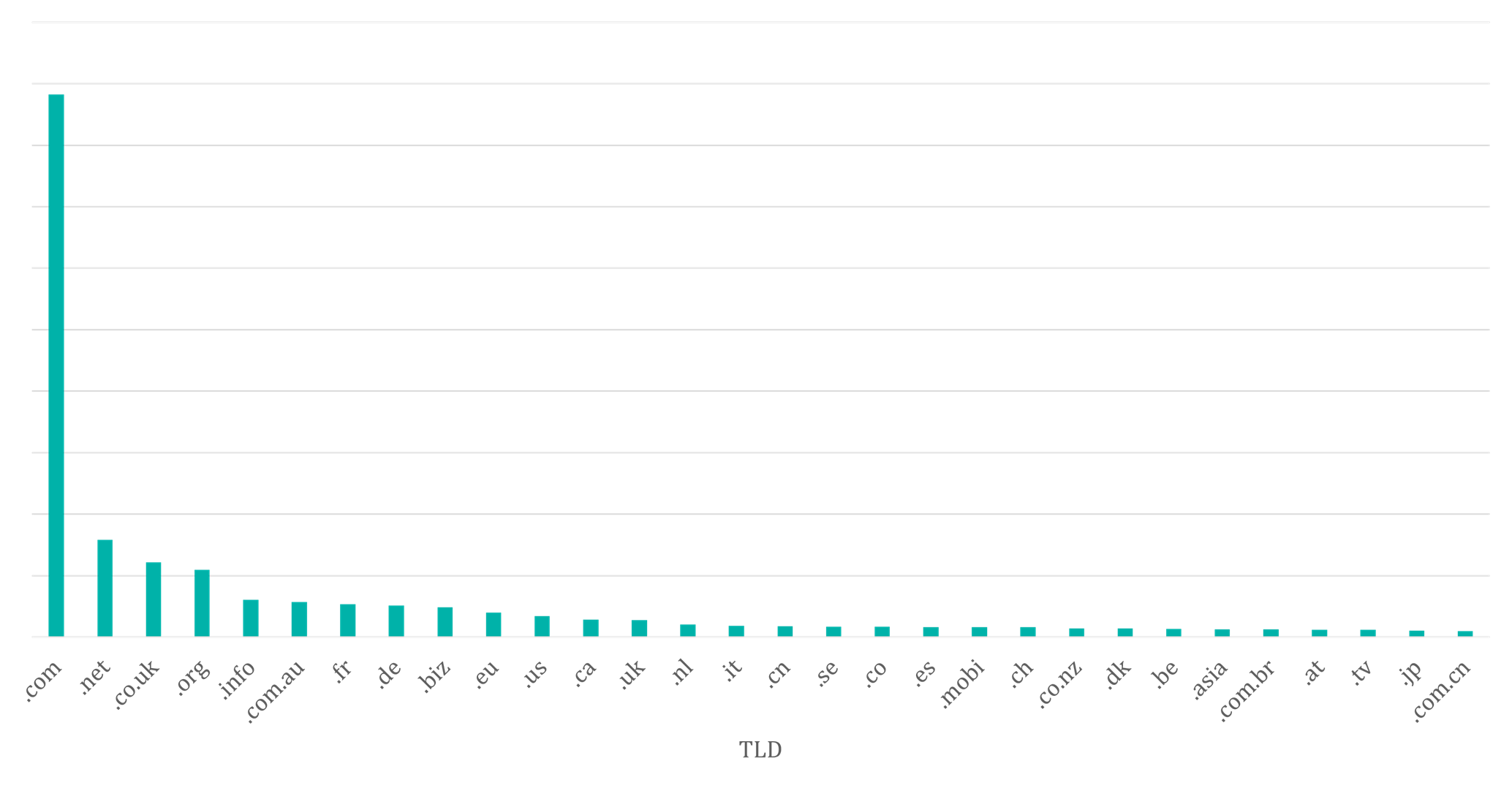

It’s also worth considering the list of top TLDs by the number of customer domains under CSC’s management (Figure 2). It’s noteworthy that only one of the TLDs from the top 30 highest-threat extensions (.CN) currently appears in this list (alongside .COM.CN).

It’s often observed that many of the highest-risk TLDs do, however, experience high levels of registration activity overall—with significant proportions associated with fraudulent use—of which much is via consumer-grade registrars, often with little legitimate activity seen by enterprise-class providers. Previous CSC studies established that most brand-related domain names on risky domain extensions are typically registered by third parties and are often involved in cybersquatting or malicious use. In one study looking at the .ICU “cousins” of the core domains of several top brands—i.e., the same second-level domain name, but on the. ICU extension—around three quarters of the domains used suspect DNS providers that were not under the control of the brand owner.

CSC recommendations

CSC has a short list of recommendations to help brand owners tackle the issues outlined in these articles.

1. Start at the foundations

Everything in cybersecurity comes back to the humble domain name. It’s vital to have a comprehensive view of your domain portfolio—what domains you have, and which are business-critical, tactical, or defensive. CSC’s Domain Management services allow organizations to manage their portfolios of official corporate domains. Deploying blocking or alerting services provides visibility of attempts by third parties to register domains containing brand-related terms. CSC’s Brand Advisory Team can consult on domain registration strategies.

2. Keep them secure

Third parties registering branded domains is just part of the issue. Keeping your official domains secure from the unauthorized changes to a domain’s infrastructure that form the basis for targeted attacks like domain hijacking, email spoofing, and phishing, is another part of the picture. As an enterprise-class provider, CSC offers several domain security solutions that allow organizations to secure their corporate domains and maintain a defense-in-depth approach as part of a robust security posture. These measures include CSC’s MultiLock, domain name system security extensions (DNSSEC), use of certificate authority authorization (CAA) records, domain-based message authentication, reporting, and conformance (DMARC), sender policy framework (SPF), and domain keys identified mail (DKIM).

3. Monitor closely for potential threats

Domain intelligence is power. Monitoring for the registration, re-registration, and dropping of brand-related domain names is highly recommended, together with using this knowledge to inform when a brand should act. CSC’s 3D Domain Security and Enforcement service does just this, encompassing a range of brand variants including fuzzy matches and character replacements. The monitoring covers a wide range of domain extensions, including high-threat TLDs. This service also monitors high-relevance domains 24×7, tracking them for relevant changes in content.

For brands where phishing is a concern, we recommend augmenting domain or internet content monitoring with a phishing protection service. This will improve coverage over areas that may not otherwise be detected, e.g., non-brand-specific domain names or unindexed internet content. CSC’s phishing detection products use a range of data sources, including spam traps and honeypots, alongside other data feeds such as customer abuse mailbox data and webserver logs. The results are fed into a correlation engine—driven by CSC’s machine learning deep search (MLDS) technology—to detect fraudulent sites by analyzing URL patterns and comparing the sites with known predictors of fraudulent content.

4. Enforce on infringements

Points 1 to 3 aim to reduce the appearance of cyber risks, but for existing infringements it’s important to have an effective enforcement solution to protect your brand. CSC’s Enforcement services includes 24×7 rapid take down of a variety of infringement types. We use a toolkit approach with a wide range of enforcement methodology options, using the most efficient and cost-effective option in any given case, while reserving other options for escalation. Effective use of enforcement enables any brand to protect its reputation, and potentially reclaim lost revenue from fraudulent activity and redirection to third-party sites.

We’re ready to talk

If you’d like more information about any of the services mentioned in this article or would like to talk to one of our experts about a how you can improve your organization’s overall domain security posture, fill in our contact form. Mention this article name and the service and issue you’d like to talk about.

[1] cscdbs.com/blog/the-highest-threat-tlds-part-1/

[2] spamhaus.org/statistics/tlds/

[3] trends.netcraft.com/cybercrime/tlds

[4] unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/top-level-domains-cybercrime/

[5] For datasets one and two, all statistics are correct as of 13 June 2022.

[6] From iana.org

[7] op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/7d16c267-7f1f-11ec-8c40-01aa75ed71a1

[8] docs.apwg.org//reports/APWG_Global_Phishing_Report_2015-2016.pdf

[9] Data correct as of June 2022